In February and March 2023 Oren Shoesmith & Rabindranath X Bhose completed their SSW X Counterflows Residency supported by Creative Scotland’s Radical Care project. The residency offered artists time, space, funding and support to develop artists practices alongside their caregiving responsibilities. Rabi and Oren take us on a beautiful journey through their winter residency.

We applied to this residency together as partners, with a reciprocal caring relationship. In this relationship, the categories of care-giver and care-receiver flow and dissolve between us. We come from communities of crip and disabled caregiving, where we look after each other. The caregiver’s residency gave us space to exist in this way, as creative practitioners in a place of production and work. It wasn’t always easy, but there were times where we were able to crip the workshop, the studio and the residency timespace. From a two-minute commute to the ground-level studio, we entered a relaxed working environment with children, partners, and dogs milling in and out; care-work, family and studio folded together. Rest is an integral practice for us, and when we enter into a studio that holds space for this, we can bring about Dream Time where we find doorways into other ways of being.

During the residency, we found ourselves considering the interplay between care and disability: disabled people often make great carers and there isn’t a hard and fast line for us between the two. SSW thoughtfully facilitated us bringing along our cat Luna, prioritising inter-species care relations just as much as they would human ones. We particularly liked this line of our contract: “the artists may bring one (1) cat.” The caregivers residency for us may have equally been renamed ‘crip residency’ or ‘queer family residency’.

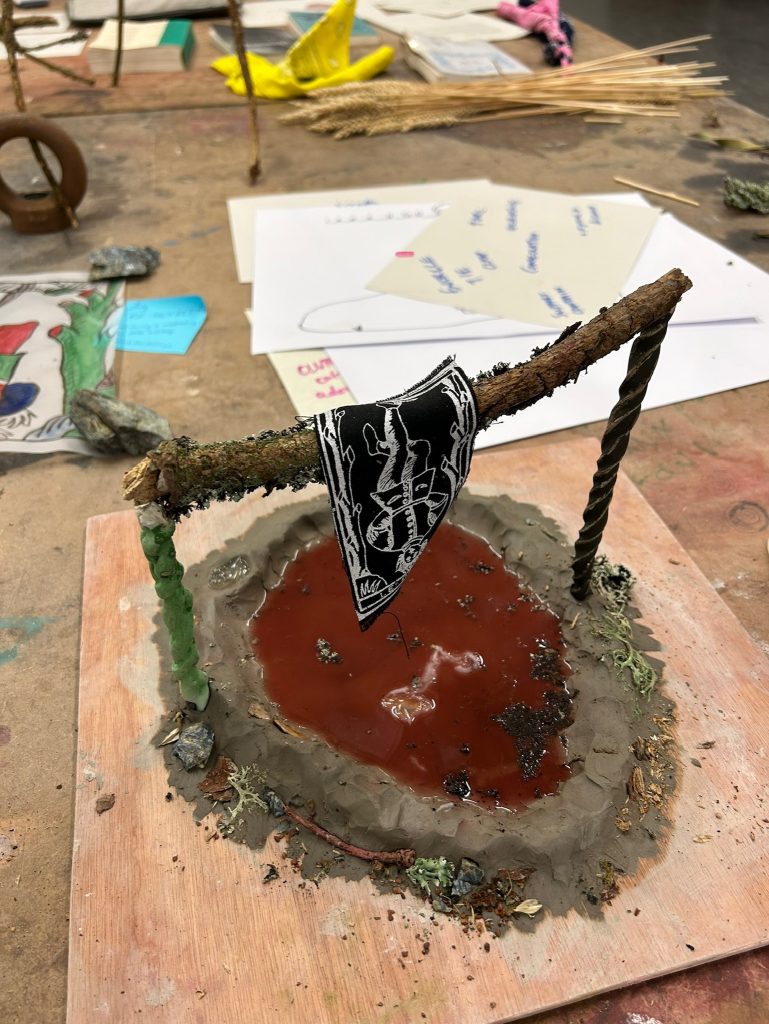

We experienced some reckoning throughout the residency, from natural causes and not-so natural ones. A big storm a few days into our time in Lumsden screamed through our windows all night, and in the morning we found it had wiped out the wifi in the studios for a couple of days due to a telephone pole falling: a reminder that we were at the mercy of the weather gods and there was no city infrastructure to mediate! We felt called to journey deeper into retreat. Rabi started working with sticks and Oren collected plaster casts from ancient chert in the nearby quarry. There was internal weather too: any personal or interpersonal conflict was amplified due to having no distractions – only the land to drive the point home if you went for a meditative walk. We also met with structural violence that is always lingering and sometimes comes down hard: we faced a brutal disability benefits tribunal and a gut-wrenching vigil for a murdered trans sibling during the month away.

After the storms had passed, we spent long times In the woods behind SSW. There is a mature birch and pine forest which we befriended on our walks. On the birch trees there are birch polypore mushrooms growing in abundance. These bracket fungi have a symbiotic relationship with the birch trees, sharing sustenance, resources, and medicine; fending off parasites and infection. It has been known since ancient times as a holistic healer with complex anti-viral, anti-fungal, anti-bacterial properties. We felt deep kinship with this coexistence. In capitalist modes of production where individualism is exalted, disabled care relations often look strange, unnerving and queer. Essential interdependent relationships can bring a maddening experience of closeness as well as opening up new horizons of mutually-sourced care. We haven’t been taught how to exist in this way and elder figures often emerge for us in non-human beings like mushrooms, plants and trees.

Our research centred around two figures from the tarot: the Hermit and the Hanged Man.

The Hanged Man is a figure suspended upside down, tied to a gibbet by one foot. Their expression is serene and contemplative despite their trapping inversion. Rabi was aware of the spiritual connotations of the card, but the more he researched the more he found the Hanged Man has agency in this position: he hangs there to dwell in the place between a material realm and a spirit realm; to gain wisdom and insight. Rabi began to practice a headstand position and relax into a view of the world upside down as he turned inwards in the rhythms and routines of an isolated rural setting.

The Hermit is a cloaked figure with a walking stick in one hand and a lantern in the other, outstretched so as to illuminate his path. His journey is devoted to seeking truth through introspection and kinship with the earth. Through the depiction of a disabled body-teacher, Oren wanted to explore the liberatory knowledge that comes from crip contexts and communities. Before the residency, he thought of the Hermit as an enlightened teacher, far off and stable. Through his research, this perception shifted to a view of the Hermit as a mad and disorientated figure. The knowledge source, like candle light, flickering and fragmented. The Hermit speaks of our wounds, and of the pain it takes to alchemise these experiences into sacred knowledge.

Even with the guiding principle of the Hermit, Oren found it hard to untangle from internally held standards of making. We talked a lot about the inherent ableism embedded into materials like clay through years of industrialization, and how the muscle memory of industrial workers is passed down through generations. This came to the surface in surprising ways through the act of producing batches of flat tiles, fighting both the clay and the limits of the disabled body. The finished tiles lay untouched, and instead the offcuts were lovingly embellished with celtic knots inspired by local pictish stones. This process became a reminder of how the body and labour of the industrial worker are so separated from creative sovereignty. Through the residency it became clear that those of us who have felt barriers accessing residency spaces, and have similar intergenerational hangovers need time and kindness to encounter these spectres held in the body as they arise. It is necessary to process the removal of these barriers in the opened up residency space to move towards a liberated making practice.

In our final week, we hosted two friends who were working on sound for an upcoming performance. It felt right to share the spacious cottage we had been offered and to invite some creative interweaving into what had become quite internal processes.

The climax of our time was a raku firing, falling at the axis of the full moon, a forecast of snow, and Saturn entering Pisces for the first time in 30 years. The colliding of elemental forces felt like a fierce blessing to bid us farewell. We invited the local community and SSW family to glaze pots with us, then gathered around the kiln in the dark underneath a swirling sky of snow and wind. The lid was popped and raised to reveal birthday cake-like tiers of pots aglow. Each smouldering ceramic object was then carefully dropped into the steaming sawdust.

As the party died down, people peeled off into the homemade sauna. We cooled down by laying in the settled snow and watched the full moon as it passed silently across the hills. Maybe this describes to you some of the existential spiritual pressure of our residency: a joyful, furious spinning in the dark.

Inspired by the birch polypore mushroom, our time at SSW gave us pause for thought about how to weave care into our working methods, how to use our interdependence to sustain our creative practices, and how to nurture environments where it becomes possible to thrive, even if only momentarily. We have since been able to deepen our practices of disability justice, understanding how our care-work and care-giving flows between us and our community as a language of love and liberation.