Some facts:

Scottish Sculpture Workshop is located in the rural village of Lumsden in the parish of Auchindoir, about an hour’s drive from Aberdeen. Less than 400 people live in the houses flanking its main street, small lanes and surrounding fields. Founded in 1979 by sculptor Fred Bushe, the workshop’s buildings occupy a site previously the location of a bakery. Originally established in 1840s, the bakery closed in early 1970s remaining vacant for a few years before Bushe began renting the premises.

At its inception, SSW had ties to the oil industry. Bushe approached local offshore companies to provide bunk beds and soft furnishings to help establish the accommodation facilities. The overalls worn by every artist who works onsite are the same as those worn by derrickhands or roughnecks on oil rigs. At SSW these baggy, protective coverings hang from hooks by the ‘Poo toilet’ (the other toilet has a dodgy flush) in the colours of red, orange and green.

According to the 1845 Statistical Accounts of Scotland the name Auchindoir is of Gaelic origin and is said to signify the ‘field of pursuit’.

It is thought this appellation derives from details relating to the death of Luthlac, son of Macbeth, King of Scots, who was slain by Malcolm in 1058 having been pursued through the valley of Auchindoir from the battlefield.

I begin by pursuing Fred’s wife, Fiona. We meet in the living room of her stone cottage just down the road from the workshop. She shared this home with Fred until his death in 2009. As her ageing black collie butts my legs, she tells me about Fred’s early motivations for setting up the Sculpture Workshop and her work as an artist and peripatetic art teacher. We speak for more than two hours, I transcribe the interview but agree not to include it here, printing the document and filing it in the archive for future researchers yet to arrive.

I begin to digest SSW’s official paper archive, a series of boxes partially compiled by Rachel Grant, a previous intern, in 2015. The archive lives in the riser cupboard of the communities room attached to the main studio. It’s shelved amongst obsolete computers, a small snooker table, various microphone stands, a knife block and new toilet seat.

This building contains the shared studio, offices, community room and ceramics workshop, and unlike other areas of the site, it has heating. Before renovations took place following a successful capital grant in 2009, working in SSW could be bitterly cold. In fact, in its past life as a bakery, the metal roof intentionally released heat; a way of regulating temperature on account of the building’s ovens. Now warm arid air circulates constantly. My lips crack and my fingers itch. These physical reactions feel antithetic to the jokes I find in letters or complaints in the old visitor notebook where the only negative comments relate to the weather: ‘just cold’. From these page to my present, the atmosphere of SSW has entirely shifted.

A notebook appears on my desk one morning. It is padded black leatherette with the word ‘Visitors’ embossed in shiny gold script. It begins 2nd August 1980. Initial pages are completed as to be expected; lists of names, addresses, brief, nondescript comments like ‘great stay’ or ‘will be back’. Then the pages devolve into more whimsical comments, there’s banter, someone writes something in the comments, another artist responds. A chain of feedback unfolds. On the inside cover someone called Robbie has scrawled in blue pen: ‘I’m writing this here to prove that I was here before the lot of you!’ To which someone else (unnamed) responds in red: ‘LIES’.

The visitors notebook expresses the personality of SSW residents but also the organisation. In approaching this administrative object with humour the artists evidence their feelings of ease, that SSW is a place of camaraderie. There are also hints of the ways in which these social bonds are often gendered. A group of Glasgow School of Art students stay – the men describe themselves collectively as ‘wild man of rock’ – whilst the women ‘Wilma Eaton and Sibylle von Halem’ are listed separately, without moniker.

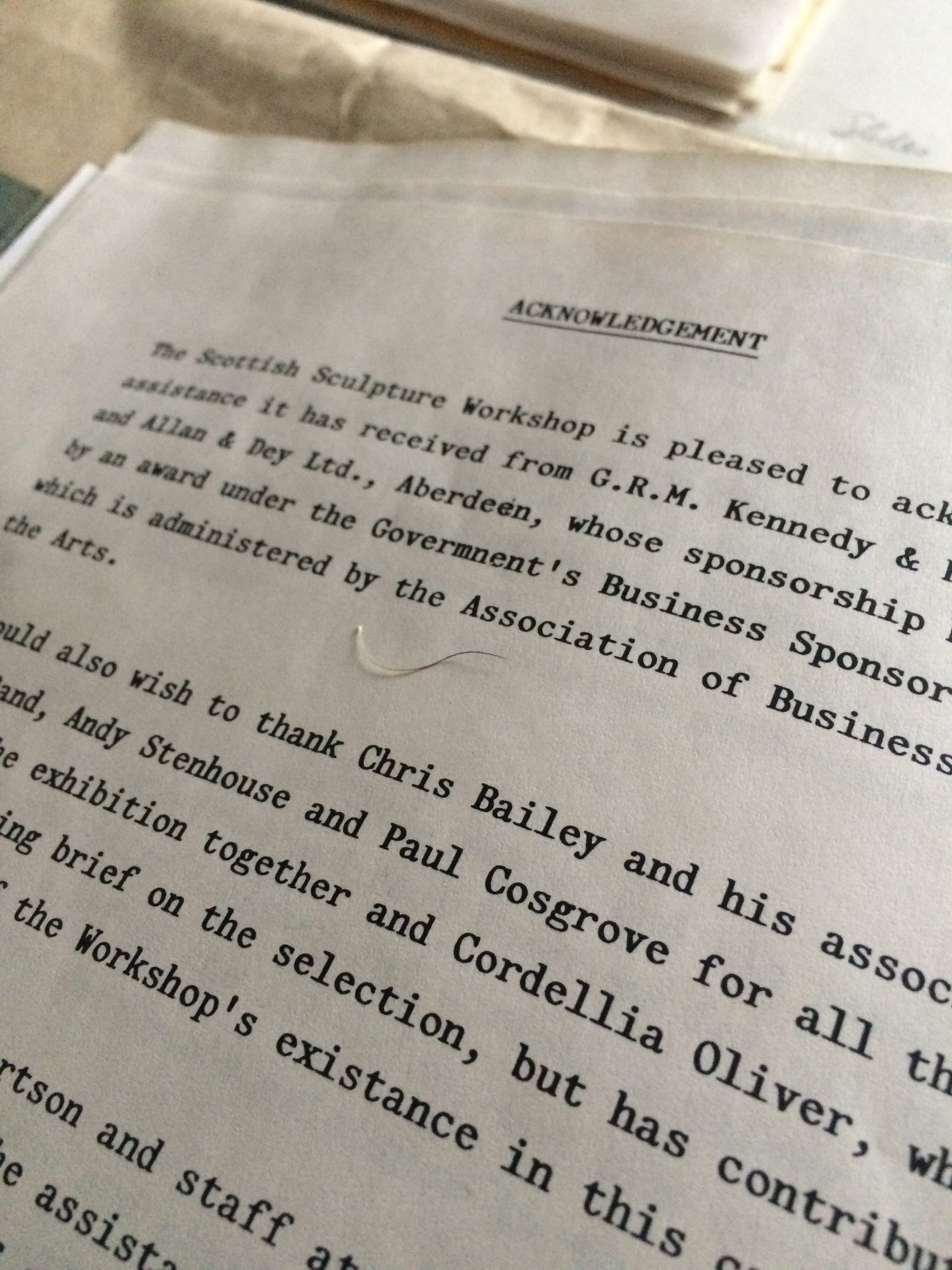

I find an eyebrow hair resting on a page of acknowledgments. It looks too long and silvery to be mine, I decide it belongs to an eyebrow, rather than any other body follicle, by the root’s pearly bud and the course shaft’s sharp twist. I imagine the hair curling dramatically from an elderly man’s furrowed brow, falling lightly and unnoticed to rest on the page as he creases his forehead in concentration. I imagine the flaking skin from my own dry fingers shedding to mingle with his. As historian Carolyn Steedman has noted, archival work is intoxicating and strangely bodily: ‘You think in the delirium it was their dust that I breathed in’.

I scan the archive’s unlabelled negatives and keep returning to the slides of women crouching over hunks of granite. I become preoccupied with a folder of photographs marked ‘Uncategorised’. Here I find large format photographs of different kinds, all their edges curling. A couple are neatly labelled with the name Cristina Biaggi. One features a large papier-mâché cave constructed in the landscape, its internal walls a shining flesh colour. The second is a sculpture of Medusa’s head carved in yew, a tangle of caramel snakes unfurling.

I google Cristina, she has a website, she’s still making work. Her book Habitations of the Great Goddess was published in 1994. I can’t tell from the archive whether she ever came to SSW, there’s nothing in her bio online. I do find a letter dated June 26th 1984 from Fred Bushe accepting her enquiry. He writes: ‘I am most interested to see your work. Unfortunately we do not have any funds – artists who come to use the facilities have to find their funding from other sources. We are fully committed until the end of 1984, but could consider a booking from you for 1985. We will hold onto your slides, etc. until you come.’ Perhaps the timing didn’t work out, or Cristina couldn’t get the money together. What remains in the archive is often a combination of chance or accident. In this case, they forgot to send Cristina’s materials back.

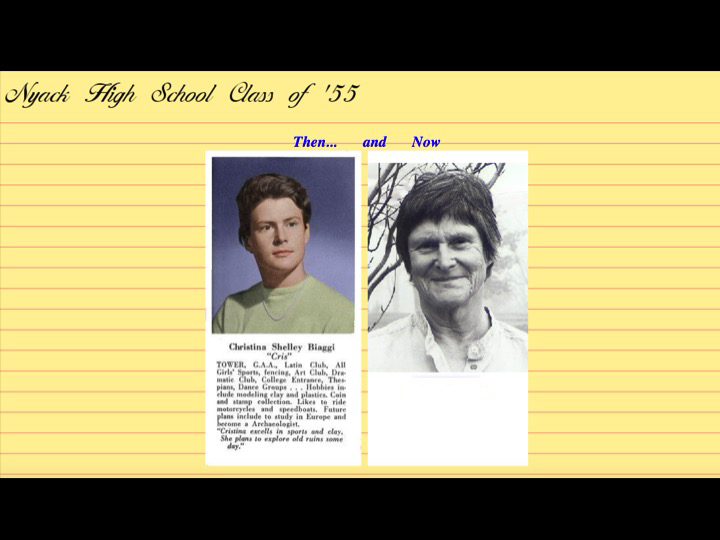

Curiosity piqued, I read recent blog posts in which Cristina describes caves as orifices – the mouths and vulvas of the earth – I bristle at the essentialism of these bodily landscape readings and the uncomfortable feminist legacies they unearth. Elsewhere, an online image search returns this:

A website dedicated to the Nyack High School class of 1955, the year Cristina graduated. Seeing Cristina’s handsome seventeen year old self, I become briefly infatuated with her, and her yearbook entry which reads ‘excels in sports and clay and who plans to explore old ruins some day.’ The full entry describes her ‘dear partner Patricia’ and I feel myself becoming more invested and then immediately ashamed of my interest.

But, as I already know, finding and discovering are acts of desire. I am thinking about Elizabeth Freeman, her concept of temporal drag, what happens to bodies when they meet across time. Freeman asks what does it mean to take pleasure in or to have fantasies about ‘rubbing up against the past’.

I want so badly for Cristina to have made work at SSW, to have been amongst the granite and bronze, walked where I walked, interrupted the phallic modernist creations with her own sculptural forms. What to do with this misplaced identification, this imagined kinship and my need to misread, over-read and read into the past?

There are always bodies which never arrive and are prevented from arriving.

We should ask ourselves now, who is not here?

I get out the archive and go on walks. One Friday it takes two hours through the fields and yellow gorse before I reach Kildrummy Castle, the sun warming my shoulders as well as the rounded backs of the treacle colored cows I pass. From 1981-1997 SSW hosted the Kildrummy Open, an annual exhibition of monumental sculptures made in the workshop and installed within the landscape surrounding the ruin. The slides in the archive show smooth planes of wood bolted into geometric shapes against a backdrop of eroded stone.

Although I rarely cry, tears form as I enter the castle’s grounds. I decide this response is in equal parts awe and fear to the wrecked structure’s scale, its material persistence and the knowledge there is so much I cannot know about the past.

I lie on the grass and look at the sky. I wish there was an audio guide. The nice woman at the visitor centre offers to drive me back to Lumsden after my visit. In the car we talk about the workshop, I ask about the Kildrummy Open, why it stopped and what she thought about the sculptures. She tells me some people didn’t like the art and the castle being in such close proximity to one another. The old against the new; it didn’t make sense.

I’m interested in what are acceptable and unacceptable ruins. I read Tim Edensor on the dismissal of industrial ruins as: ‘spaces of waste, that contain nothing, or nothing of value […] saturated with negativity as spaces of danger, delinquency, ugliness and disorder.’ Edensor wants to re-imagine the industrial ruin as somewhere in which ’multiple relationships between things, space, non-human life and humans. The intensities and energies released by these elements impact upon and penetrate each other to produce an ensemble of multiplicities.’

I interview Mrs Petrie, the oldest resident of Lumsden, or so she thinks, asking about her memories of working at the site when it was a bakery. In her mind it has only ever been a bakery, nothing but fields before.

I record her on my phone, but the quality isn’t great. I find another recording online, produced as part of the oral history project Lumsden Stories co-produced with SSW in 2015, you can listen to it here: http://lumsdencommunity.co.uk/story-working-at-the-bakery/.

Remember, someone has usually come before you.

Humans cannot live on raw grain; we don’t have the teeth or stomachs for it, therefore we must transform grains into food by cooking. The basic methods for making grains palatable are sprouting, fermenting, roasting, boiling and baking.

Eating and making art both need heat. Sculpture consumes: fuel, time, raw material.

It’s impossible to make anything without extracting something from the earth.

I read the workshops as archives, containers of history, trying to write about the traces and gestures they hold. I speak with and observe SSW’s artist residents, interns, technicians, and administrators, writing down their anecdotes and the descriptions of their processes.

‘The body is neither – whilst also being both – the private or the public, self or other, natural or cultural, psychical or social, instinctive or learned, genetically or environmentally determined’

– Elizabeth Grosz, Volatile Bodies: Toward a Corporeal Feminism

My experience is dominated by the absence of another. I fall for a girl who wears orange. We meet on my first night. I say hello, mildly irritated by the disruption to my evening routine. Walking into the bothy I immediately regret not changing my stained jogging bottoms, that I did not fix my hair or face.

In truth, we spend only a handful of days together at SSW. My first week is her last. When she returns briefly during my second visit, my feelings solidify. We drink wine, she cooks for me. We coax a slow hedgehog across the road, smoke cigarettes in midnight sleet. I want to kiss her but decide that in positioning her body against the wall, hips tilted away from mine, she isn’t interested.

The following afternoon I fold her number, written on a scrap of newspaper into the pocket of my jeans. And then she is gone (again) and I mope around for weeks. Her traces everywhere. In ceramics I find a shelf of her unglazed experiments, a dusty peach tile with a flickering candle design and the words ‘Still awake, turns out’ scratched into its surface.

I go on more walks to distract myself. Drawn to other kinds of ruins I find and break apart tarry barn owl pellets which lie on the floor of an abandoned farm cottage like a regurgitated carpet.

Some more facts (and speculation):

In Lumsden village there are a few traders and handicraftsmen; and blacksmiths, carpenters, masons, and tailors, are distributed through the different estates; but the mass of the population is agricultural, and the people are sober, frugal and industrious in their habits.

– The New Statistical Account of Scotland (1845), Volume XII – Aberdeen, United Parishes of Auchindoir and Kearn

I fall for the foundry too. Pouring bronze and cooper, heart racing, mascara melting. Listening carefully after to the pings of cooling metal, pulling sooty bogies free.

Eden Jolly is SSW’s own living archive and workshop gatekeeper. He compiled the eight ‘yearbooks’ held in the community room. These slim, black plastic folders chronicle activities at the workshop from 1986 – 2002. Yellowing plastic sleeves their surfaces puckered with the room’s dry heat show pixilated photographs hastily arranged on a now outmoded word processor. I flick through these yearbooks in my first week but don’t find out Eden made them until the end of my residency. Pre-photoshop or smart phone, the folders are full of intimate snaps taken on a film camera; visitors caught off guard striking poses or shrinking from the lens. I read the captions (full of innuendo and wise cracks) in Eden’s voice. I ask him why he stopped making them. He shrugs and mentions Facebook; their usefulness diminished with the advent of social media. His other extra curricular pursuits include Squennis; a steampunk mashup, part squash, part table tennis, installed in a corner of the gang hut.

During my time at SSW I ask Eden all the questions I can think to ask about pouring metal. He replies generously always, his answers full of chemistry, and tall tales of a disparate international community bound by their love of melting metal; a shared historical practice. One afternoon he shows me the following film. It shows Eden and others in Sweden pouring molten iron into a block of ice:

After pouring bronze, Meg, an artist from Skye makes me a dinner of tuna nicoise. She tells me about her interest in bees. She is trying to study them as a guide for how to live, taking inspiration from the way they make and care. Bees as a method. We talk about the pour earlier that day, she said it was ‘atavistic’, meaning ancestral, a fundamental kind of recall. I like how the word sounds so I look it up and of course, etymologically it comes from the Latin ‘atavus’ meaning ‘forefather’. SSW’s forefather, Fred Bushe, still has his head attached to the building; rendered in cast iron and fixed on a spike.

It’s impossible to stay at SSW without thinking about what or who has worked here before. From the metal girder in the studio lined with small sculptures; failed objects and experiments, to the melted plastic pot handles in the kitchen, their screws loose and jangling from use. My last duvet had a blooming black ink stain from a previous sleeper’s dribbling pen. People pass through this place temporarily, they make it their home for a short while. Other people – the technicians and administrators – witness these guests, careful not to get too close. SSW is an institution but it’s also a domestic space; residents sleep under its roof and everyone, staff and residents, eats together in the bothy. Saying goodbye can be difficult in these contexts where the lines between life and work are blurred.

Before I go to SSW friends warn me about Lumsden: a small village, quiet, not much going on.

Over the last forty years SSW has weathered financial crises, loss of local population and industry, changes to management, policy and funding. In addition artistic trends have shifted and environmental concerns have meant there is no longer such an appetite for hulking modernist sculptures carved from granite or wood. Despite this SSW has persisted, the site developing piecemeal. Although the foundry was specifically built in the 1990s, its remaining workshops and office spaces have been remodelled and adapted from previous uses over time. Across the yard from the foundry, the gang hut is a shed roughly the size of a shipping container. Constructed from OSB board it was originally built as a project space by the artist collective Ganghut in 2008. Ten years later and this unit is either a room of requirements or holding pen for the unwanted, depending upon who you speak to. The metal and wood workshop, referred to by staff as ‘the red shed’ is spoken of in a mournful tone inflected with frustration. The shed’s roof sags when it rains flooding the interior and its workbenches hosting old equipment. The forge tucked into the corner of the yard is sheltered by a rusting patchwork of corrugated steel, to the untrained eye the scraps of sheet metal or collection of rods arranged here awaiting manipulation appear abandoned. Elsewhere, actually abandoned artworks collect around the perimeter of the site, weeds sprouting along the carved edges of stone or rusting iron. These artworks may have been experiments or simply forgotten; left by residents deemed too large, heavy and expensive to transport, photographed for their portfolio with the hope they might be sold and find a permanent site in the future. In this sense, all the artworks remaining at SSW are the ones not remembered.

The truth is that SSW’s workshops are crusty. It is provisional and continually self-cannibalising – using parts of itself for alternative needs when required. During my stay pieces of wood from the outdoor sauna shower get used as material and shredded office paper becomes paper clay. It is a site of contradictions; workshops are restricted by the methods of material processes (there is a right way to pour bronze, a right way to slip cast) and yet, despite these regulations, they are constantly adapting to meet the needs of those who activate them. Without wishing to romanticise these coping strategies there is also a danger of pathologising them. What if limitations, the need to compromise and the revisionist attitude of SSW staff, catalyse the imagination of residents? What if making works best when improvising, one fuelling the other, hand in hand?